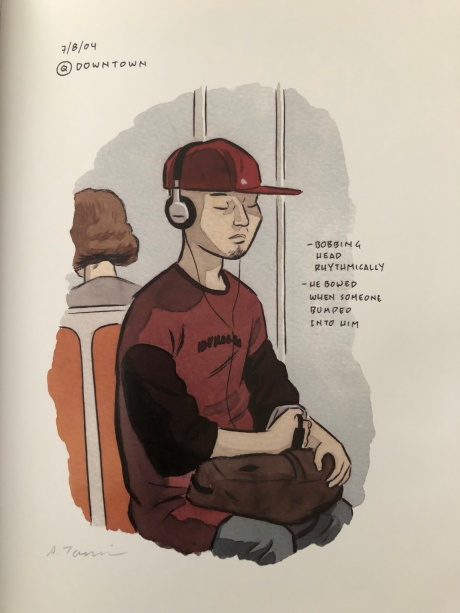

From Adrian Tomine’s New York Drawings

I have been thinking about silence a lot this week, partly inspired by a wonderful piece on the subject – “Listening for Silence With the Headphones Off” – in Pitchfork.

There is much to reflect on in the article. My favorites include a quote from the poem “Self Portrait at 28” by David Berman:

“All this new technology

will eventually give us new feelings

that will never completely displace the old ones

leaving everyone feeling quite nervous

and split in two.”

And also this:

“Music can both drown out the noise of living and fill an uncomfortable absence.”

The writer of the piece – Mark Richardson – mentions that silence can be both an expression of power and of powerlessness, and suggests that it might be framed as listening to listening. The latter intrigues, and I continue to ponder on this.

My own fascination with silence began at the moment when I acutely “lost” (a ridiculous word for describing something for which I had no culpability) hearing in one ear. Nerve deafness, from which there has been no recovery. Since then I struggle to locate sound, and my perception of music has of course changed. But I am pretty used to it now, even the tinnitus has become part of who I am. There is much noise in the world that I can selectively blank out. If I lie on my hearing ear side, I imagine that I am listening to silence. I have come to cherish such moments.

I am also exploring a different kind of silence – the quietening of my mind through Buddhist meditation. This is a challenge, and will be a life-long one, if even ever achievable. But the process itself is a hopeful one. In Thich Nhat Hanh’s book on the topic, he states:

“There’s a radio playing in our head, Radio Station NST: Non-Stop Thinking. Our mind is filled with noise, and that’s why we can’t hear the call of life…”

Thich Nhat Hanh aspires to “Noble Silence”, the kind of silence that is also a presence, to a being there that is therapeutic and healing.

Other types of silence can be destructive, and perhaps stem more from a imposed – self or other – silencing.

“There was silence in the room for several minutes and this silence felt like a kind of suffering to Gustav.”

from Rose Tremain, The Gustav Sonata

I have spent many years in therapy, which has been a transformative experience. Those years of weekly sessions were akin to a stepwise and cumulative breaking of a life-long imposed silence.

For me, walking into the analyst’s room comes from a place of stillness. When we are born, we exit the silence of the womb and a lifelong cacophony of noise ensues. When we die, we return to a place of stillness, or so it seems. The therapeutic space is a liminal one, a microcosm of a lived life, bookended by silence.

Words are critically important to me, but I have come to see both them – spoken and unspoken – as inextricably linked to silence. Even if not acknowledged as such, sound depends on its counterpart for its existence. Music cannot be heard without the pause that precedes it. Silence is part of everything that we say, and as implicitly part of our communication as the words that emanate from it.

Alexander Newman considers that:

“There can be no psychotherapy except on the basis of silence – even the ‘talking cure’ presupposes silence.”

Similarly, from Gregory Ala Isakov’s song, Caves:

“Did I hear something break / Was that your heart or my heart / Like when the earth shakes / Then the silence that follows”

I am not sure that I agree with Wittgenstein’s statement “All I know is what I have words for”. Having spent my life living in words, I am now increasingly curious about, and keen to explore, the wordlessness of silence.

“For once on the face of the earth,

let’s not speak in any language;

let’s stop for one second,

and not move our arms so much.

It would be an exotic moment

without rush, without engines;

we would all be together

in a sudden strangeness.”

from Pablo Neruda, Keeping Quiet

CQ